Rendering Memory: How AI Can Honour History Without Distorting Humanity

Preserving Truth in a Digital Age

“AI slop” is practically everywhere, and every day it seems as though authenticity is being lost, one plagiarized image at a time. Aside from the ethical implications of scraping data without the consent of the original artist or author, AI is also distorting history.

Recently, a fellow historian told me how an AI-created image came up in his social media feed. This was not just any image, though. The “creator” had featured a scene from the Holocaust: An American soldier carrying a prisoner on the day the Allies liberated Dachau.

Why AI-Generated Images Distort History and Undermine Archival Truth

As an artist, my disdain for the commodification of image-making is nothing new. As a conflict historian, I felt a flash of anger that such a dark period in history had been reduced to clickbait. Although the Allies did free Dachau prisoners at the end of the war, the scene in the social media post never actually occurred.

The first thing that makes this type of content concerning is the fact that photos from this period in history already exist. There is absolutely no need to dilute experiences so raw, so painful, into AI slop when the archival records are already there. What pushed this into being ethically irresponsible to me was how the AI model constructed the image. The American soldier is holding a prisoner who is thin, but not anything resembling the emaciated bodies found at Dachau. The figures in the picture are artificially posed and even rendered in a way that is supposed to make them appear attractive.

AI treated one of history’s greatest atrocities the same way it would apply photo retouching to a product or magazine model. Now, image-making and the human condition become commodified—because AI has no capacity to understand the human condition. AI produces outputs by recognizing human patterns, but it lacks the nuance necessary to translate that humanness through words or pictures. Instead, AI dilutes collective memory with images that are not real, and worse, that appear much too polished.

By making the Holocaust (or any atrocity) aesthetically palatable, it loses meaning. If enough of this kind of content gets shared, it bolsters false narratives that already exist about how the Holocaust “wasn’t that bad.” This has already happened in the history of enslaved Black Americans. Visiting plantations as a scenic tourism destination (and sharing the photos) creates false associations linking an idyllic environment and slavery. If a plantation is pretty enough to use as a wedding venue, then slavery must not have been so bad, right?

How AI Can Respectfully Amplify Historical Memory

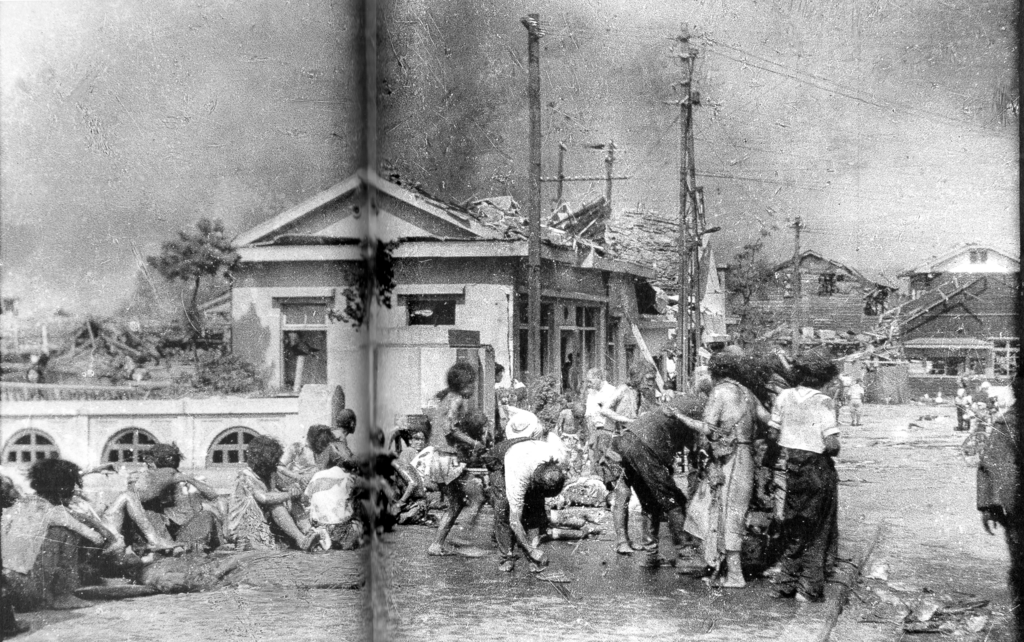

AI can be used responsibly to contribute to the collective memory. While researching the photographic and oral history of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, I came across the image of survivors on the Miyuki Bridge. The survivors, many barely clinging to life, are gathered at a small, makeshift aid station. The photo was part of a set of five taken by Yoshito Matsushige within the first three hours of the bombing. Amid catastrophe, Matsushige was compelled to preserve this moment of human suffering.

(Image credit: English: Matsushige Yoshito日本語: 松重美人, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

In Matsushige’s memoirs, he wrote that he was “born to be there at that moment” to witness “the wounded, their eyes fixed on [him]…as if they wanted [him] to tell the whole world what was happening.”

Here is where AI plays a meaningful role in Matsushige’s story. Much of his photo is left obscured and ambiguous. Who is on the bridge? Did anyone in this photo survive? What is that girl holding in her arms?

The documentary Hiroshima: The Day the Sky Fell answers these questions. Using photogrammetry (extracting spatial data), AI-based visual reconstruction, and 3D modelling software, historians extrapolated details from the grainy photo and brought Matsushige’s image to life.

Facial modelling made it possible to identify living subjects of the photo, who filled in informational gaps with their testimonials. Posture estimation added context for where those individuals were standing. The digital reconstruction of Miyuki Bridge and the surrounding debris anchored a moment to a real place. The result was a valuable contribution to the archival record and collective memory.

I distinctly remember this project being meaningful to me as both a conflict historian and a human. While researching a field hospital at Ninoshima (just off the coast of Hiroshima), I discovered that Sunao Tsuboi, a powerful voice of anti-nuclear activism during his lifetime, was one of the survivors taken to the island for medical treatment. The Day the Sky Fell explains what happened to Mr. Tsuboi before he was transferred to Ninoshima.

Mr. Tsuboi’s story mattered to me because here was one of the most well-known (for me anyway) hibakusha (atomic bomb survivor), confirming that he was in one of the only photos taken the day the bomb was dropped. Being able to piece together stories like these also has a meaningful impact on the hibakusha community and their families.

Reimagining Canadian Archives to Tell Impactful Stories

Unlike traditional archival methods that rely on static photographs and documents, 3D reconstruction and AI modelling can offer an immersive way to engage with history. While archives preserve authenticity and require viewers to interpret context, digital reconstructions embed spatial relationships and environmental detail directly into the experience. Passive observation is transformed into active exploration.

These digital techniques could be powerful when applied to Canadian archival photos, such as those documenting Indigenous-settler relations, wartime mobilization, or early urban development. For example, photogrammetry and AI could reconstruct scenes from the War of 1812 along the Niagara frontier or visualize the lived environments of residential school survivors using historical images and oral histories.

By layering visual data with cultural context, these reconstructions can deepen public understanding and foster empathy, connecting historical record to lived experience.

Responsibly Using AI in Canadian Humanities to Preserve Authenticity and Integrity

All this is to say that AI and other technology advancements are tools, and the intent behind how someone uses those tools matters, both ethically and historically. Canada has a policy framework for AI use, although it does not explicitly cover what is an appropriate usage of historical reference images. Despite the absence of those guardrails, we can still hold ourselves to a high standard of authenticity.

The humanities do not need to become less human because we are introducing newer technologies. On the contrary, we can make the humanities more human in how we use technology. Only by the power of our individuality and critical thinking skills is this possible.